Allergies, also known as systemic hypersensitivity

1906: The word “allergy” (allos = other, foreign, strange; ergon = work, reaction) was coined by Clemens von Pirquet in a short essay in the Münchner Wochenzeitschrift. The Viennese pediatrician described it as an exaggerated response of the immune system.

Today, the term refers to an immune-mediated and allergen-specific hypersensitivity reaction.

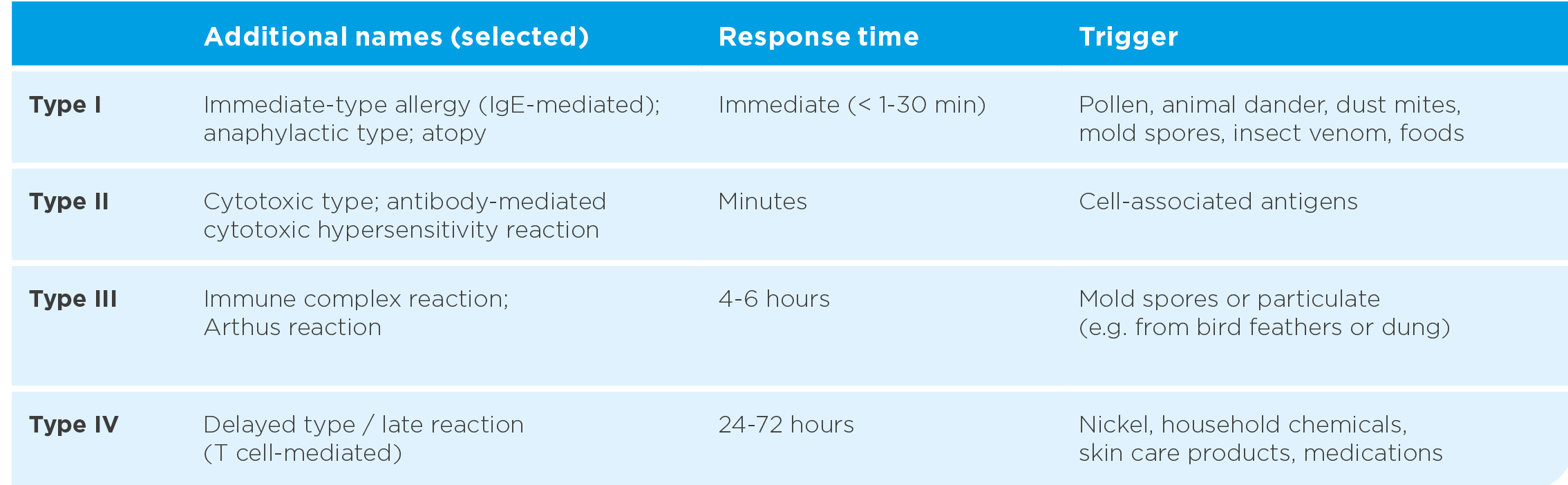

Allergies are typically classified into one of four types according to the Gell-Coombs model. Since the classification was first published, our understanding of allergies has greatly expanded, which is why the EAACI and the WAO have proposed a new structure for distinguishing hypersensitivity reactions in accordance with the reaction that triggers the immunological mechanism. Both classifications are explained below.

-

The Gell-Coombs classification

Hypersensitivity divided into four hypersensitivity reactions

The four types of hypersensitivity reactions (tab. 1), of which type I–III are antibody-mediated and result in a humoral response, whereas type IV is cell-mediated, cannot always be clinically distinguished.

Type I hypersensitivity reactions are often viewed as “classic allergies”. The allergic reaction of type I starts with the production of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies against fundamentally harmless antigens (=allergens). Many of the allergens that trigger type I reactions are low-molecular-weight, highly water-soluble proteins that are part of larger complexes such as animal hair or pollen. They enter the body via the mucous membranes of the airways or via the digestive tract.

Normally, the body produces IgM, IgG or IgA antibodies that remove the allergen without causing any symptoms. However, IgE production leads to local or systemic (affecting the whole body) atopic reactions, ranging from itching and difficulty breathing to shock or even death. Type I hypersensitivity quickly triggers an immune response upon contact with the allergen, usually within a few seconds to 30 minutes (immediate type). Responses of this type include allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, allergic asthma, acute urticaria and IgE-mediated anaphylaxis.

Table 1: Classification of hypersensitivity reactions according to Coombs and Gell (based on (1, 2–5, 6–8))

-

Classification according to WAO and EAACI

Hypersensitivity according to immune mechanism

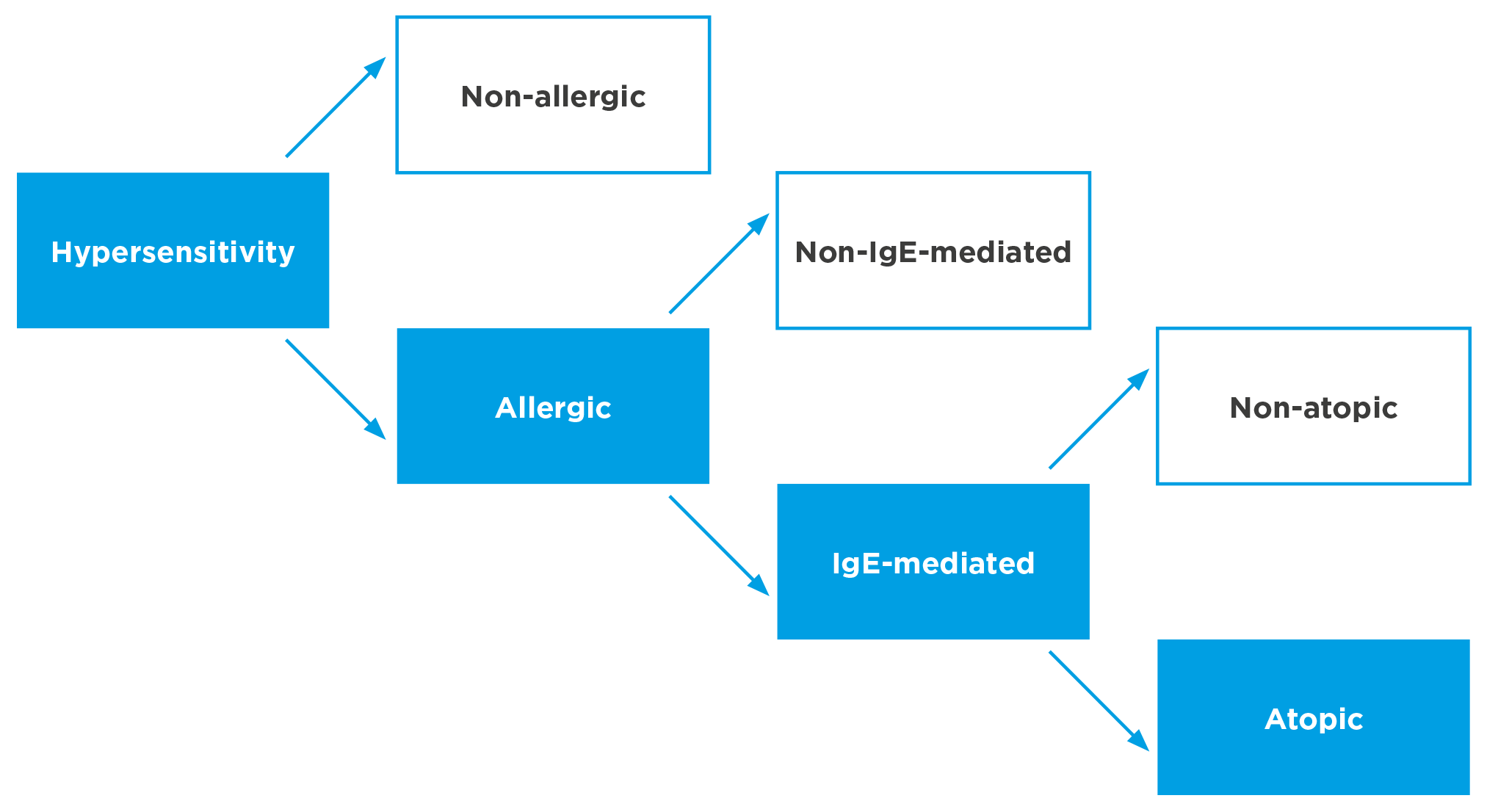

Hypersensitivity produces objectively reproducible signs and symptoms in predisposed patients* that are caused by exposure to a specific stimulus that is easily tolerated by healthy patients.

It can be subdivided into “non-allergic hypersensitivity”, which is not based on an immune mechanism, and “allergic hypersensitivity”, which is caused by immune mechanisms. It can be antibody-mediated or cell-mediated, although most allergic hypersensitivity reactions involve IgE antibodies (IgE-mediated allergy).

They are distinguished from “non-IgE-mediated allergic reactions”, such as allergic contact eczema (T cell-mediated) or allergic alveolitis (IgM-mediated). IgE-mediated allergies are associated with atopy, for example reactions to insect stings, helminths or drugs. For the diagnosis of atopy, evidence of IgE-mediated sensitization (e.g., in the patient’s serum or by skin prick testing) is required. Fig. 1 shows an overview of this classification.

Fig. 1: Classification of hypersensitivity reactions according to EAACI position statement of the EAACI nomenclature task force (based on (1, 9, 10))

-

Risk factors

Both endogenous and exogenous factors can impact the development of allergic diseases and their severity.

Endogenous factors

- Genetics: There is a genetic predisposition for the development of allergic diseases

- Age / sex: Boys are more likely to be affected in childhood than girls, while women are more likely to be affected in adulthood.

- Comorbidities: Atopic diseases progress over time in what is known as the atopic march. Children with eczema often develop asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis later in life.

Exogenous factors

- Climate: Changes in climate can increase the risk of allergic reactions

- Allergen concentration: An increased allergen concentration in the environment also appears to have an impact on asthma and rhinitis

- Place of residence: The prevalence of atopic diseases is higher in urban areas than in rural areas

- Air pollution: Air pollutants such as ozone, nitric oxides and particulate matter are more common in large cities and can damage the mucous membranes of the airways, making it easier for allergens to enter the body

- Smoking: Tobacco smoke appears to be even one of the root causes of allergic diseases

- Socioeconomic status: A higher socioeconomic status increases the morbidity rate

- Siblings: Having siblings tends to decrease the risk of allergies

- Type of birth: C-sections, especially if the parents have allergies, can increase a child’s risk of developing asthma

- Medication: It appears that children are more likely to develop asthma in the first few years of life if their mothers took paracetamol during pregnancy.

-

Epidemiology

The incidence of IgE-mediated allergic diseases is generally underestimated and the number of affected patients is increasing worldwide, especially in industrial nations. The socioeconomic costs of workers’ inability to work due to allergic respiratory disease are considerable. The more advanced the disease, the more difficult and costly it is to treat.

Global prevalence

Allergic diseases affect 20 to 30 % of the world’s population, and even 40 % in some regions, according to WAO estimates. That equals approximately 2 billion people, and the incidence and prevalence of asthma and rhinitis continues to increase worldwide. Based on the dramatic increase over the past 60 years, 4 billion people will be affected by 2050. Allergies have also been described as “the epidemic of the 21st century”.

Allergic rhinitis alone affects 500 million individuals, 200 million of whom also have asthma. Both of these conditions should be considered systemic inflammatory diseases. They often occur together, with over 80 % of asthmatics reporting rhinitis symptoms and 10 to 40 % of patients with allergic rhinitis also having asthma.

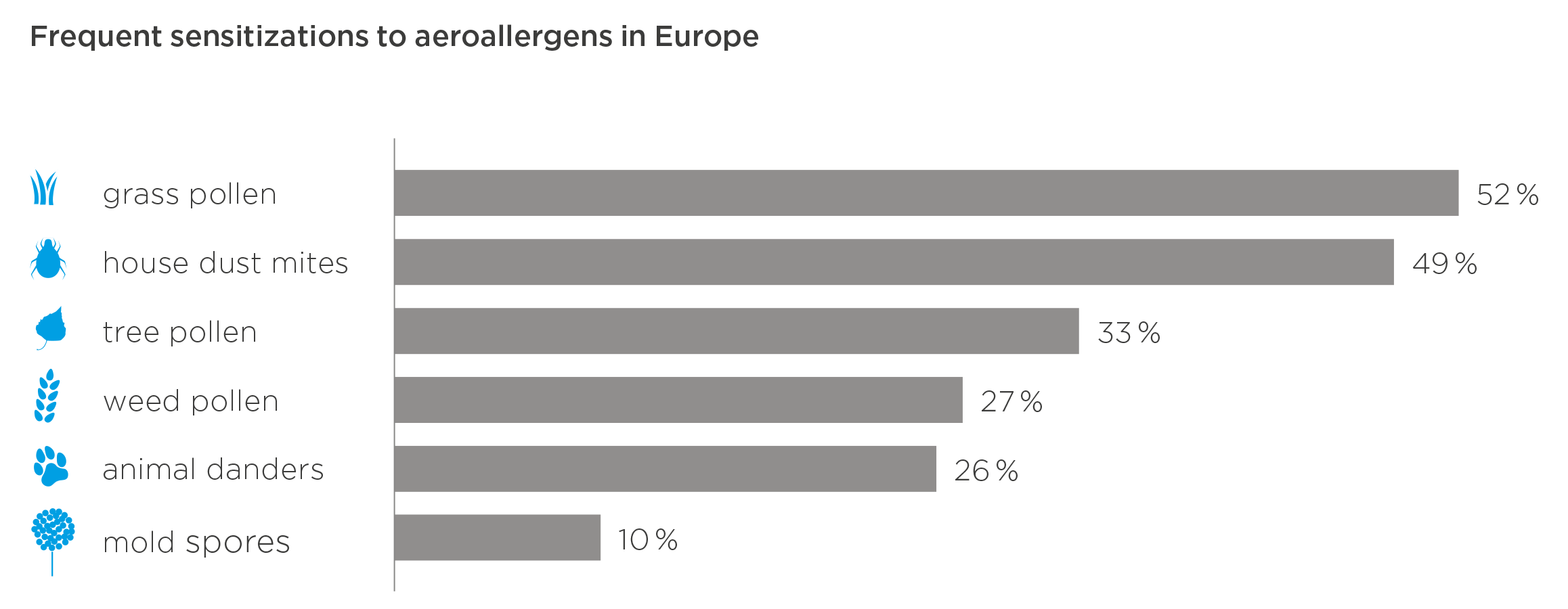

Fig. 4: Percentage of patients in Europe found to be sensitized to a selection of aeroallergens using serologic IgE analyses (based on (15))

Prevalence in Germany, Europe and other industrial nations

The prevalence of allergic sensitizations, as measured by the presence of allergen-specific IgE in the patient’s serum or by skin prick testing, often exceeds 40 % in Europe, with similar data in the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Larger countries tend to have local variations. Today, allergies are the most common chronic disease within the European Union. Fig. 5 shows official data on the allergy prevalence in various European countries.

In Europe, about 20 % of the population suffer from allergic rhinitis and about 5 to 12 % have asthma. The prevalence of allergic rhinitis is 8.5 % in children aged 6 to 7 years and 14.6 % in adolescents aged 13 to 14 years. One in four children has at least one allergy. A Europe-wide study showed that the prevalence of clinically confirmed IgE-mediated allergic rhinitis was 21.5 % in Spain, 24.5 % in France, 26 % in the United Kingdom and 28.5 % in Belgium. Depending on the study, the prevalence in Germany is estimated to be between 13 and 24 %. The prevalence of allergic rhinitis across Europe is therefore 23 %. That is nearly 103 million people in the EU, with more women than men and more young people than older people being affected.

Fig. 4: Percentage of patients in Europe found to be sensitized to a selection of aeroallergens using serologic IgE analyses (based on (15))

-

Impact in terms of health economics

Despite their prevalence, potential severity and immense impact on quality of life, public opinion often trivializes allergic diseases. Even the patients themselves often fail to take their disease seriously enough to seek medical advice, which means they do not receive a differential diagnosis or adequate treatment.

A study on allergic rhinitis in Germany showed 50 % of allergy sufferers to be undertreated. Another publication suggests that up to 90 % of workers in the EU who suffer from an allergic respiratory disease or allergic skin condition are not receiving adequate treatment. Lack of awareness heightens personal suffering and increases the risk of developing a comorbidity, causing high socioeconomic costs.

An American study calculated the average annual productivity loss per employee caused by allergies in dollars from December 2001 to September 2002, and compared it to other diseases. Allergic rhinitis ranked highest, costing six times as much as diabetes and ten times as much as coronary heart disease. Because of the high costs associated with their severe comorbidities, disease management programs generally focus on diabetes and congestive heart failure. However, due to their high prevalence, diseases with comorbidities that are often trivialized incur similar or even higher costs.

According to a model calculation, the cost of lost working time and reduced concentration and performance caused by allergic diseases alone could be as high as 55 to 150 billion euros in the EU, depending on the prevalence and level of impairment. Treatment according to guidelines, on the other hand, could save between 50 and 140 billion euros.

-

- References-

- Pschyrembel. Allergie; 2018. Available from: URL: https://www.pschyrembel.de/coombs/K0224/doc/.

- Gell PGH, Coombs RRA. Clinical Aspects of Immunology. Oxford: Blackwell; 1963.

- Averbeck M, Gebhardt C, Emmrich F, Treudler R, Simon JC. Immunologic principles of allergic disease. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007; 5(11):1015–28.

- Mak TW, Saunders ME, editors. Primer to the immune response: (Second Edition). Acad. cell update ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2011.

- Ott H, Lange L, Kopp MV. Kinderallergologie in Klinik und Praxis. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

- Ring J, Bachert C, Bauer CP, Czech W, editors. Weiβbuch Allergie in Deutschland. München: Springer Medizin, Urban & Vogel GmbH; 2010. (vol 3).

- Saloga J, Angerer P, Klimek L, Buhl Roland, Mann W, Knop J, editors. Allergologie-Handbuch: Grundlagen und klinische Praxis . Stuttgar t: Schattauer; 2006.

- Madore A-M, Laprise C. Immunological and genetic aspects of asthma and allergy. J Asthma Allergy 2010; 3:107

- Johansson SGO, Hourihane J, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy: An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001; 56(9):813–24.

- Akdis CA, Agache A, editors. Global Atlas of Allergy: European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; 2014.

- Mak TW, Saunders ME, editors. Primer to the immune response: (Second Edition). Acad. cell update ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2011. Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature 2008; 454(7203):445–54.

- Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature 2008; 454(7203):445–54.

- Palomares O, Akdis M, Martín-Fontecha M, Akdis CA. Mechanisms of immune regulation in allergic diseases: The role of regulatory T and B cells. Immunol Rev 2017; 278(1):219–36.

- Shamji MH, Durham SR. Mechanisms of allergen immunotherapy for inhaled allergens and predictive biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140(6):1485–98.

- Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Crevel RWR, Pickup J. Too clean, or not too clean: the Hygiene Hypothesis and home hygiene. Clin Exp Allergy 2006; 36(4):402–25.

- Poulos LM, Waters A-M, Correll PK, Loblay RH, Marks GB. Trends in hospitalizations for anaphylaxis, angioedema, and urticaria in Australia, 1993-1994 to 2004-2005. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2007; 120(4):878–84.